Modern Katanas vs. Antique Nihontō

Spend five minutes in any sword community and you’ll stumble into the same tired argument: modern katanas versus antique nihontō, as if one must be crowned champion and the other dismissed as pretender.

The whole debate usually collapses into romanticism pretty fast. Antique blades get wrapped in mystique—forged by legendary smiths, tested in actual combat, survivors of centuries. Modern katanas swords get treated like they’re auditioning for a role they’ll never quite deserve. But framing it this way misses the entire point.

The question shouldn’t be “which is better?” It should be “what do you actually need this sword to do?”

Because here’s the truth: modern katanas and antique nihontō serve completely different purposes in completely different worlds. Comparing them directly is like judging a violin against a guitar because they both have strings. You can do it, but why would you?

How the Katana’s Role Has Changed

Antique nihontō were born into a world of warfare. They were designed to cut through armor, settle disputes, and mark social standing. As Oscar Ratti and Adele Westbrook document in Secrets of the Samurai, a samurai’s sword wasn’t just a weapon—it was wrapped up in ritual, clan identity, even spiritual significance. These blades had jobs to do, and those jobs were serious.

Modern katanas exist in a fundamentally different reality. They’re training tools for iaido, battōdō, tameshigiri—disciplines codified and standardized by organizations like the All Japan Kendo Federation. They’re collector’s pieces celebrating Japanese culture and craftsmanship. They show up in films and anime, shaping how millions of people picture Japanese history. Some people buy them because they want a tangible connection to a philosophy or tradition they respect.

None of this is wrong. But it means you can’t compare these swords without accounting for their completely different contexts. It’s the typewriter-versus-laptop problem all over again—the answer to “which is better” depends entirely on what you’re trying to accomplish.

Why Age Isn’t Proof of Excellence

Let’s cut through some mythology: old doesn’t automatically mean superior.

We love to imagine historical Japan as a place where master smiths worked with almost supernatural skill, producing blades that modern makers can only dream of replicating. And sure, some smiths were genuinely brilliant. But as Leon Kapp and his co-authors detail in The Craft of the Japanese Sword, they were also working within serious limitations—inconsistent iron ore, rudimentary metallurgical knowledge, production methods that varied wildly by region and era.

Most historical swords weren’t masterpieces. They were made to be functional. A blade that could survive a battle, hold an edge reasonably well, and not shatter on impact—that was the standard. Exceptional blades existed, absolutely, but they were exceptional precisely because most weren’t.

Modern metallurgy has changed the game entirely. Historical tamahagane typically contained 0.5-1.5% carbon with significant impurities, while modern high-carbon steel can be controlled to ±0.05% carbon content. Traditional heat treatment varied by roughly ±50°C; modern processes can be controlled to ±5°C. This doesn’t erase what historical smiths accomplished with the tools they had. But it does obliterate the notion that older automatically means better.

The Invisible History of “Failed” Blades

Here’s what really warps our perception of historical quality: we only see the survivors.

Think about all the mediocre katanas forged in, say, 1650. Where are they now? Destroyed in battle. Reforged after damage. Worn down to nothing through centuries of polishing and use. Lost to war, fire, neglect. The swords that make it to museum collections or private hands today—like those documented in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston’s Japanese sword collection or the Japanese Sword Museum in Tokyo—are overwhelmingly the exceptional ones: blades valuable enough to preserve, famous enough to protect, beautiful enough to treasure.

This creates massive survivorship bias. When we look at antique nihontō, we’re seeing a greatest-hits collection. Meanwhile, every modern katana—the masterwork and the mediocre—exists right in front of us. We judge the entire modern output against only the best historical examples and then act surprised when the comparison feels lopsided.

If we could see the full spectrum of historical production—every battlefield blade, every hastily forged replacement, every sword made by a smith having an off day—we’d have a much more realistic picture of what “typical” actually meant. But those blades are gone, leaving us with a distorted view of the past.

Artifact vs. Instrument: What Are You Actually Buying?

This distinction matters more than almost anything else when you’re deciding what to buy.

An antique nihontō is a historical artifact first and a sword second. As Colin M. Roach explores in Japanese Swords: Cultural Icons of a Nation, these blades are cultural documents that tell stories about the era they came from, the person who made it, the hands it passed through. These blades are finite. Once they’re gone, they’re gone forever. That makes them invaluable for study and preservation, but it also means owning one comes with real responsibilities and limitations.

A modern katana is a functional instrument. It’s built to be used. You can train with it, test it, learn from it. You can make mistakes without destroying something irreplaceable. Modern smiths create these blades knowing they’ll see actual use—in dojos, at cutting events, in serious study.

Problems arise when you buy an antique expecting a training tool, or when you buy a modern blade expecting it to carry historical weight. Match your expectations to reality. A gorgeous antique you’re too nervous to touch isn’t serving you. A modern blade that disappoints you for lacking a pedigree is being judged against the wrong standard.

Ownership Is Not Equal

Owning these swords day-to-day? Completely different experiences.

Antique nihontō are demanding. Museum-grade preservation requires controlled environments at 40-60% humidity and 18-22°C temperature, according to conservation standards followed by institutions like the Victoria and Albert Museum. You need strict handling protocols. Professional polishing only—and that’s expensive, time-consuming, and removes approximately 0.01-0.05mm of steel per session. One careless moment, one mistake, and you can permanently damage both the blade’s value and its historical integrity. You’re not just maintaining a sword. You’re preserving cultural heritage.

Modern katanas are forgiving. They tolerate more environmental variation. Maintenance is practical and learnable. You can train with them, mess up, figure things out, all without the constant terror that you’re destroying something priceless.

Neither approach is wrong. But the ownership experience is night and day. If you want a sword you can actually use regularly, an antique is probably a terrible choice. If you want to own a piece of living history and you’re ready to treat it with appropriate care, an antique might be perfect. Just know what you’re signing up for.

Polish, Patina, and Perception

There’s something undeniably compelling about an antique blade. The way light catches steel that’s been shaped by centuries, the subtle color variations that only time creates, the weight of presence that comes from holding an object that’s witnessed history—antique nihontō have visual gravitas that modern blades usually can’t match.

But here’s the thing: that aged patina isn’t the same as functional sharpness. A blade can look stunning under museum lighting and still be far from ideal for cutting. The reverse is equally true—a modern katana might look plain or too bright at first glance, but that pristine geometry and precisely controlled temper line represent functional excellence.

We’re wired to associate age with value, to read wear as authenticity. That’s not wrong. But it’s incomplete. A modern blade’s lack of historical weathering isn’t a deficiency—it’s just a different aesthetic reflecting different priorities. Once you understand what you’re actually looking at, both become easier to appreciate on their own terms.

Smith vs. System: Human Mastery and Process Reliability

Antique nihontō carry the fingerprints of individual makers. The way a particular smith folded steel, the signature patterns in the hamon, the thousand small choices that no two craftspeople make quite the same way. This variability is part of their charm and their historical value. But it also means quality varies dramatically. Some historical smiths were genuine masters. Others were competent professionals doing difficult work under challenging conditions.

Modern production works differently. As documented by the All Japan Swordsmith Association (Zen Nihon Tōshō Kai), contemporary smiths combine traditional techniques with controlled heat treatment that delivers specific hardness levels consistently. Precision tooling enables geometric accuracy that hand-forging alone struggles to achieve. Quality control catches problems before blades reach buyers. Talented modern smiths still make crucial artistic decisions, but the baseline of reliability is higher and more predictable.

Both matter. The human mastery visible in a historical blade connects us to individual skill and living tradition. The process reliability of modern production means practitioners can train with confidence. Neither invalidates the other. They’re just different balances between artistic expression and functional consistency.

The Hidden Modifications of Antique Blades

Something that surprises people buying their first antique: the sword you’re looking at probably isn’t in its original form.

Many antiques have undergone suriage—shortening—over the centuries, as Kokan Nagayama documents extensively in The Connoisseur’s Book of Japanese Swords. Maybe the blade was damaged near the tang and cut down to remove the flaw. Maybe it was reshaped to fit changing fashion or fighting styles. Repeated polishing, necessary for maintenance but removing microscopic steel layers each time, means many antiques have lost significant material over hundreds of years. An antique blade may have undergone 50 or more polishings across its lifetime. The geometry you see today might be quite different from what the original smith intended.

This isn’t necessarily a problem. These modifications are part of the blade’s story, evidence of its use and evolution through time. But it creates an interesting irony: modern katanas, produced to replicate historical designs, often preserve the original design intent better than the actual antiques they’re modeled after. That “authentic” museum piece might be shorter, thinner, and shaped differently than when it left the forge.

Understanding this helps you appreciate both types more accurately. An antique tells a story of change and adaptation across centuries. A modern blade captures a design frozen in steel. Both are valid. They’re just not the direct comparison they appear to be.

Legal, Ethical, and Cultural Considerations

Before you even think about buying an antique nihontō, understand the complications.

Many countries, Japan included, have export restrictions on antique swords. Japan’s Cultural Properties Protection Law (amended in 1975 and 2004) regulates the export of culturally significant items, and swords made before 1953 generally require special export permits. These laws protect cultural heritage and prevent historically significant artifacts from scattering to the winds. Navigating these regulations takes research, documentation, often significant money. And even if you can legally acquire and own an antique, you’re taking on the responsibility of preserving it for future generations. These aren’t just swords—they’re cultural heritage that belongs, in some meaningful sense, to everyone.

Modern katanas avoid these dilemmas entirely. You can buy them without worrying about export paperwork or heritage laws. You can use them, modify them, even destroy them (though I wouldn’t) without ethical complications. This doesn’t mean you respect tradition any less. It just means you’re engaging with it in a way that doesn’t risk harming irreplaceable historical objects.

For a lot of people, this freedom matters. You can train seriously, make mistakes, learn without the weight of cultural stewardship on your shoulders. That’s not nothing.

If Samurai Existed Today

Imagine samurai existed right now, with access to all our modern materials, tools, and knowledge. They’re still training for combat, but they’ve got options the historical samurai never dreamed of.

Would they choose swords made with traditional methods and historical materials, or would they embrace modern metallurgy? Would they value romantic authenticity over performance? Would they prefer blades matching historical aesthetics or ones optimized for modern training demands?

I think they’d be pragmatic as hell. Historical samurai weren’t romantic about their equipment—they used what worked. If modern steel offers better edge retention, why wouldn’t they use it? If controlled heat treatment provides more consistent performance, why reject it for less reliable methods?

This thought experiment isn’t about diminishing tradition. It’s about challenging our assumptions about what “authenticity” even means. The samurai spirit wasn’t about using old things because they were old. It was about mastery, effectiveness, constant refinement. Seen through that lens, modern katanas might be more authentic to samurai philosophy than we give them credit for.

Tradition as a Living Line, Not a Frozen Relic

People get this wrong constantly: they think tradition means doing things exactly as they were done in the past, unchanging and pure.

That’s not how real tradition works. Tradition is a living line running from past through present into future, and it stays alive precisely because each generation adapts it to their circumstances while preserving the core essence.

As William H. Coaldrake explored in his study “Traditional Japanese Swordsmiths in Modern Japan” for Monumenta Nipponica, modern smiths aren’t betraying tradition when they use better steel or more precise temperature control. They’re preserving tradition by keeping the katana relevant, ensuring new generations have reasons to learn about these blades, train with them, understand their significance. They’re not imitators copying dead forms. They’re practitioners evolving a living art.

This matters because it changes how we evaluate modern katanas. Instead of asking “is this as good as what came before?” we might ask “does this serve today’s practitioners while honoring the principles that made these swords significant?” Framed that way, many modern blades succeed brilliantly.

Continuity requires adaptation. A tradition that refuses to change becomes a museum exhibit—admired but not lived. Modern katanas keep the tradition breathing.

The Honest Buying Question

Before you buy any sword, ask yourself what you’re actually drawn to.

Is it the history? That tangible connection to a specific era, knowing this object existed when events you’ve read about were unfolding? Is it performance? The desire to train seriously, to cut, to develop real skill with a tool designed for that purpose? Is it symbolism? The way a katana represents discipline, artistry, a philosophical tradition you admire? Is it usability? The practical need for a blade you can handle regularly without constant anxiety?

Neither antique nihontō nor modern katanas are wrong choices. But mismatched expectations absolutely are. An antique sitting in a case because you’re too nervous to handle it isn’t serving you if what you really wanted was a training partner. A modern blade that disappoints you for lacking historical provenance isn’t the problem if what you actually wanted was to own a piece of history.

Be honest with yourself about what draws you. Choose accordingly. The sword that fits your actual needs will bring you far more satisfaction than the sword you think you’re supposed to want.

Two Legacies, Two Truths

Antique nihontō and modern katanas represent two different legacies. Both carry truth.

Antique nihontō are echoes of the past. They connect us to specific moments in history, specific smiths, specific traditions. They’re finite, irreplaceable, precious. They demand respect, care, understanding. They’re not casual-use tools—they’re cultural documents we’re privileged to preserve.

Modern katanas are tools of the present. They’re made for training, learning, use. They let us engage with the katana tradition actively rather than passively. They’re not trying to be antiques. They’re trying to be functional, reliable, and accessible while honoring the principles that made these swords significant in the first place.

Respecting both without forcing a hierarchy means understanding that “better” depends entirely on context. An antique nihontō isn’t better than a modern katana—it’s different, serving different purposes and meeting different needs. Same goes in reverse.

Understanding context leads to better appreciation and smarter ownership. When you know what you’re looking at, why it exists in that form, and what it’s meant to accomplish, you can evaluate it fairly. You can choose the right sword for your purposes. And you can appreciate both antiques and modern blades for what they actually are rather than what you wish they were.

That’s not just a better way to think about katanas. It’s a better way to engage with tradition itself.

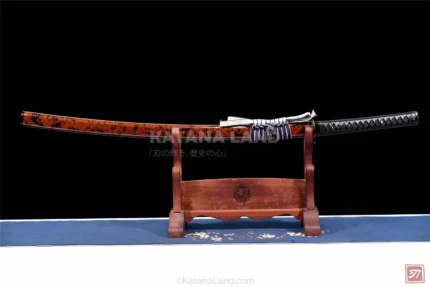

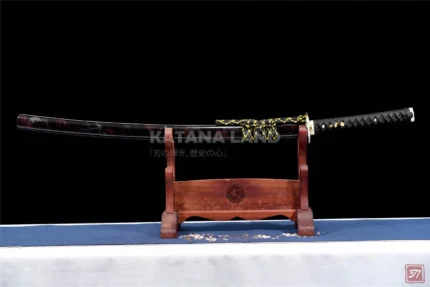

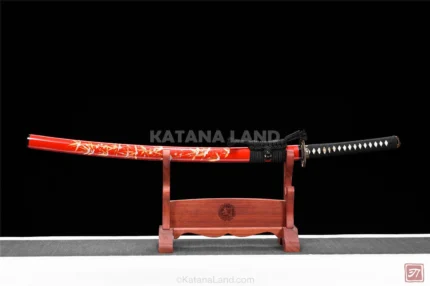

Modern Katana Swords by KatanaLand.com

-

Aoi Katana$440.00

Aoi Katana$440.00 -

Akai Hoko Katana$270.00

Akai Hoko Katana$270.00 -

Blue Demon Katana$730.00

Blue Demon Katana$730.00 -

Akazome Sakura no Yoto Katana$300.00

Akazome Sakura no Yoto Katana$300.00 -

Aoi Yurei Katana$240.00

Aoi Yurei Katana$240.00 -

Aoi Kinsuke Katana$360.00

Aoi Kinsuke Katana$360.00 -

Aoshi Kyuchoten Katana$730.00

Aoshi Kyuchoten Katana$730.00 -

Akaketsu Shou Katana$740.00

Akaketsu Shou Katana$740.00 -

Bamboo Harmony Katana$1,240.00

Bamboo Harmony Katana$1,240.00 -

Agarwood Katana$300.00

Agarwood Katana$300.00 -

Beast King Conquest Katana$320.00

Beast King Conquest Katana$320.00 -

Choko Katana$230.00

Choko Katana$230.00